IMAGE: theblowup at Unsplash

Reading Time 9 minutes

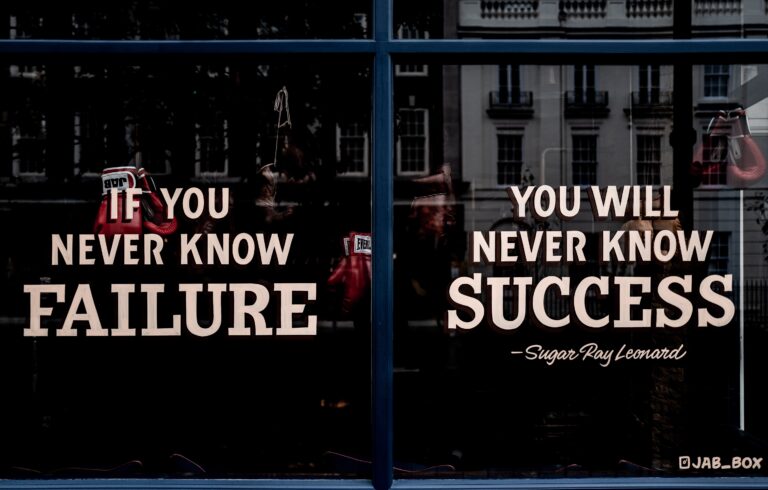

About innovation, failure comes with the territory, a bit of fun about the Museum of Failure and how companies create psychologically safe innovation environments for Good failure.

Value: Understanding how to create a better working approach to failure that serves us all well.

Innovation Failure: Why Innovation is (mostly) a losing game.

I first encountered this salutatory statistic when reading for my thesis on innovation management. The title of the 1997 article by Greg Stevens and James Burley, says it all: “3000 Raw Ideas = 1 Commercial success.”

The decay rate from the Raw Idea to the new product launch is steep. There are lots of reasons both good with organisations involved in the hard task of making money from new offerings.

The bad ones are wrapped up in poor organisational routines and processes such as letting bad ideas go too far and consuming precious resources. There are also hits on our innovators who sweat blood and cry tears for projects they believe in.

We can flip that bad for good, by, giving up earlier, releasing that precious resource to do more Good projects and helping our innovators to want to do it all again.

Enter, the Museum of Failure

Psychologist, Samuel West curate the museum because innovation needs failure.

It features a collection of “failed” products and services that didn’t create the value that was promised, or even hoped for.

Very public failures at the museum include Google Glass the wearable head device streaming information and content into the wearer’s eye. And Olestra by Pringles maker Procter and Gamble as a health play. Who’d have thought that the non-absorbing oil would have, erm, unexpected consequences from not being absorbed by the human body?

The growing collection consists of over 150 failed products and services.

Think about all the reasons a Failure can happen.

All these new products came with great promise, with very smart people involved and likely hundreds of millions placed to return billion-dollar businesses.

And it wasn’t because these people were stupid, even though we can laugh at these “obvious” failures…

Think of a time your team failed.

How did that go for you?

The museum is worth a browse at https://museumoffailure.com/

The Experience of Google in Building the Perfect (Innovation) Team

Of course, I followed the Trail of Failure to Google.

In 2012, Google was one of the most public examples of how studying workers can transform productivity. It became driven to know how to build “the perfect team” under a project code name Aristotle.

Project lead Abeer Dubey said ‘‘We had lots of data, but nothing was showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.’’

There was a clue in what psychologists and sociologists called “group norms” – the traditions, behavioural standards and unwritten rules that govern how we function when we gather.

MIT and Carnegie Mellon put it differently wanting to know if there is a collective IQ that emerges within a team that is distinct from the smarts of any single member. What interested the researchers most, however, was that teams that did well on one assignment usually did well on all the others. Conversely, teams that failed at one thing seemed to fail at everything.

The researchers eventually concluded that what distinguished the ‘‘good’’ teams from the dysfunctional groups was how teammates treated one another.

“As long as everyone got a chance to talk, the team did well,” showing that Good teams carried high social sensitivity.

This led to a discovery by Harvard Professor Amy Edmondson on what has been called Psychological Safety and it is important for innovation leaders to know about.

Psychological Safety is “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up. It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.”

This was why the Google Good teams did well, despite not being those with the highest individual IQ scores.

Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently)

So why do innovation teams in organisations sometimes fail? For lots of reasons, but let’s drill into this Psychological Safety phenomenon because it has a real impact. And because we can tune our organisations and our behaviour to better innovation working.

What is Failure?

Failure, in organizations and elsewhere, is a deviation from expected and desired results and it includes both avoidable errors and the unavoidable negative outcomes of experiments and risk-taking.

An important reason that most organizations do not learn from failure may be their lack of attention to small, everyday organizational failures, especially as compared to the investigative commissions or formal ‘after-action reviews’ triggered by large catastrophic failures. Small failures are often the ‘early warning signs’ which, if detected and addressed, may be the key to avoiding catastrophic failure in the future.

A learning organisation is FAILING ONE.

Learning from failure is a hallmark of innovative companies but, as noted above, is more common in rhetoric than in practice. Most organizations do a poor job of learning from failures, whether large or small.

There are solid reasons why companies do not learn from failure.

But first, think of an organisation as simultaneous social systems and technical systems that can be inherently difficult to understand.

Individually, we have strong incentives not to fail, drilled into us from an early age. Let’s face it, managers have an added incentive to disassociate themselves from failure because most organizations reward success and penalize failure.

So we have to reset our “organisational selves” in the context of the company culture.

Three processes can help an organisation learn from failure.

Leaders have to set the ground in three core organizational activities through which organizations learn from failure,

- Identifying failure,

- Analyzing failure, and

- Deliberate experimentation.

EDF the energy utility found only five to ten per cent of dissatisfied customers choose to complain following service failure; instead, most simply switch providers.

IDEO: ‘Fail often to succeed sooner’ and ‘Enlightened trial-and-error succeeds over the planning of the lone genius.

Meaning and Learning for Innovation Leaders

Fail Well not Fast.

Set up your unit so that small failures provide early warning signs and a wake-up call to avert disaster further down the road. Here are some ideas to start you off on becoming failure tolerant,

- Reframe Failure. When the failure comes, what do you do about it? What process will you follow what message do you give, and what failure-appropriate rewards will you provide?

- Check your leadership behaviour. Set standards and expectations; is what you say about failure and do about it congruent?

- How will you instil in people that failure has a purpose; to redeploy your precious resources and their energy and talent on wins?

- Set up a learning system for when your innovation “failed”.

- What do you do when failure “cover-ups “ happen? This is the real negative behaviour.

- What is your Failure toolbox – the approach to learning and understanding what “went wrong” and Why? Do post-project learning reviews.

- Target an expected Failure rate – to drive radical thinking. If you’re not failing maybe you’re not radical enough.

- Design experiments to learn. How can you learn to get the signal that failure is coming, sooner?

Liked this article?

CLICK HERE to stay ahead and get regular Innovation Success Insights delivered straight to your email box

Want to know more?

Rob Munro delivers strategic innovation services to companies, universities and government agencies giving business and innovation leaders the practices, tools and confidence to achieve best-in-class innovation results. Please contact me to discuss ways to bring greater effectiveness to your innovation processes.

Read more about my service to organisations for innovation planning in improving innovation results.

Further reading

“3,000 raw ideas equals 1 commercial success!”, Stevens, Greg A; Burley, James, Research Technology Management; May/Jun 1997; 40, 3; ABI/INFORM Global

Museum of Failure, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_Failure

What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team – The New York Times, 2016

Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently): How Great Organizations Put Failure to Work to Innovate and Improve, Mark D. Cannon and Amy C. Edmondson, Long Range Planning 38 (2005) 299-319